The U.S. Wanted to Use Bat Bombs to Fight the Japanese in World War II

By on Apr 04 2018

I can only imagine what was going through Lytle S. Adams' mind when, upon hearing news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he thought, bats.

An Idea Takes Flight

On December 7, 1941, Adams, a dentist and inventor from Irwin, Pennsylvania, was vacationing in the American Southwest. During this trip, he visited the Carlsbad Caverns. Located in the Guadalupe Mountains of southeastern New Mexico, Carlsbad Caverns National Park is a prime destination for spelunking and the home to a million bats. All these bats certainly left an impression on Adams, as we would later find out.

When he heard about Pearl Harbor on the radio, he was shocked and immediately made plans to head back home. But the impressive bat colony he left in Carlsbad never truly left him; he couldn't shake those bats. Perhaps they flew around in his mind late at night as he stared up at the cavernous ceilings of his lodging. Maybe he heard their leathery wings rustling in strange bed sheets. There's also the chance that he had a close call with one and feared the notion of a rabies shot. In either case, the bats clung to him with their little bat claws and then came an idea: bat bombs.

As Adams would later recall in a 1948 interview, he asked himself, —Couldn't those millions of bats be fitted with incendiary bombs and dropped from planes? What could be more devastating than such a firebomb attack? "

On his way back up to Pennsylvania, he made a pit stop at Carlsbad and captured a few Mexican free-tail bats. The most common species of bat in North America, these little guys (weighing in around 9 grams) can carry external loads more than twice their own weight.

Don't ask me how you travel halfway across the U.S. with several bats, but he managed to do it and once he was home, he set to work.

A Bizarre Proposal

Adams started by learning everything he could about these little flying mammals. He even uncovered some truths behind bat myths: they're not blind, they don't get tangled in hair, they don't attack people, and they're usually not dangerous to humans (you know, unless you give them bombs).

Tadarida brasiliensis, Mexican Free-tailed Bat

The more he learned, the more he became convinced that the U.S. could use bats as bombers. Lytle Adams was so convinced of his idea that on January 12, 1942, he sent a letter to the White House with his plan on how to get revenge on their WWII enemies: bat bombs.

His plan entailed strapping tiny incendiary bombs to the bats, who would then inadvertently carry the bombs into the all the nooks and crannies of Japan.

In later years, Adams said in an interview, "Think of thousands of fires breaking out simultaneously over a circle of forty miles in diameter for every bomb dropped. . . Japan could have been devastated, yet with small loss of life. "

The bats themselves being an exception, of course— but animal rights in the 1940s were not what they are now.

War can bring a country together and inspire people who otherwise could not be bothered with their Nation's state of affairs. During this time, hundreds of citizens were writing to the government with proposals for their own warfare ideas. Naturally, many of these were very bizarre and impractical. However, the bat bombs were not one of those filed away in White House garbage bins. In fact, after going through top-level scientific review, —the government greenlighted the idea. It was one of the very few civilian ideas that made it to President Roosevelt's desk given the thumbs-up. Adams' idea likely got so far because he happened to know Eleanor Roosevelt.

WWII Bat Bombers

On April 16, 1942, Donald R. Griffin, a special-research assistant, sent a memo to the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) of the National Inventors Council titled 'Use of Bats as Vectors of Incendiary Bombs'. He described Adams' proposal as using —very large numbers of bats, each carrying a small incendiary time bomb. The bats would be released at night from airplanes, preferably at high altitudes and the incendiaries would be timed to ignite after the bats had descended into low altitudes and taken shelter for the day. Since bats often roost in buildings, they could be released over settled areas with a good expectation that a large percentage would be roosting in buildings or other inflammable installation...when the incendiary material was ignited. "

The U.S. Government concluded that Lytle Adams was not a nut and proceded with the proposal.

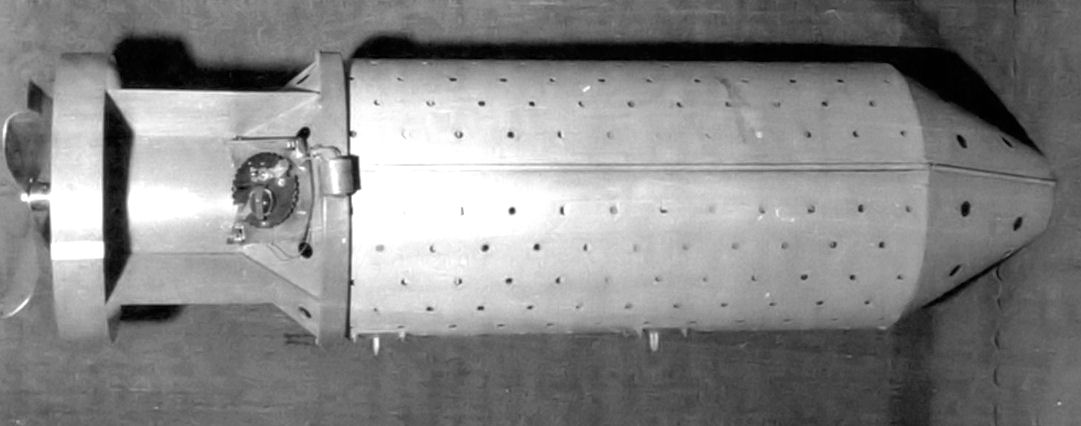

Bat bomb canister developed to house the hibernating bats.

Adams and a team of naturalists got to work experimenting. The team decided to use the Mexican free-tail bat for the project because although they were smaller than other breeds, they were the most populous and easy to get in high numbers. They also concluded that the bats would be able to fly with a payload between of 15 to 18 grams.

Adams took a few bats and dummy bombs to Washington, where he sufficiently impressed the U.S. Air Force. The scheme to —determine the feasibility of using bats to carry small incendiary bombs into enemy targets " became Project X-Ray.

The Army captured thousands of bats for project X-Ray and designed tiny bombs for them. But other aspects of the system were far more complex. While they determined they would ship them cooled (to keep them in hibernating mode), figuring out how to release them in midair was another problem. The tests did not go as planned and the Marine Corps took over the program and testing in December 1943. After 30 demonstrations and spending $2 million, they canceled the project.

I bet the bats were relieved.

Sources:

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/201...