Could a 150-Year-Old Patent Be the Answer to Saving American Steel?

By on Mar 22 2017

An apparent decline in U.S. steel production has been a crisis for many Americans.

U.S. Steel Corporation, for instance, plans on permanently closing one of its Tubular Operations mills in Lorain, Ohio, come June 2017. Democratic Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur has written to President Donald Trump calling for his administration's assistance in securing the stabilization of the U.S. steel industry. " The importation and use of foreign steel, coupled with the global overcapacity of steel, creates challenges for many American steel producers and steelmaking communities (like Loraine, Ohio).

President Trump has previously stated his plans to help the steel industry and its workers (contrasted with China's plans on cutting half a million heavy industry jobs this year). As part of his plan, Trump has pledged to spend $1 Trillion on U.S. infrastructure projects and has issued a directive stating that new American pipelines must be made with American steel. " This directive does not apply to the Keystone XL or Dakota Access pipelines (the latter which is nearly complete), as technically they are not new " projects.

But the future for steel might not be so grim.

China has already started to cut its excess production and has slowed its exportation as the United States and European Commission have imposed anti-dumping duties on steel products. According to Bloomberg, industry profit outlook has revived and product demand is growing all before Trump's infrastructure projects have even come into effect.

There's another glimmer of hope on the horizon for steel production that is worth mentioning, which involves the potential for slashing steel costs: strip casting.

How an Old Idea Might Work with New Technology

With our continual use of contemporary steel, it's easy to forget that its production and use are antique. At least as early as 13th century BC, blacksmiths found that iron was transformed into a harder and stronger material when left in charcoal furnaces. Throughout history, plenty of other civilizations have utilized steel, from Asia Minor to East Africa to Rome.

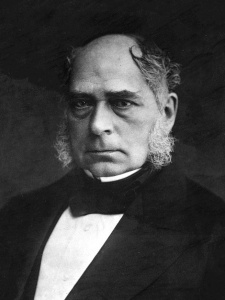

Modern steelmaking and mass production, however, began in the 19th century with Henry Bessemer.

Sir Henry Bessemer: the (Other) Man of Steel

Henry Bessemer was an English inventor most notable for developing a steelmaking process that would become the backbone of its mass production. In the 1850s, Bessemer developed a system to blow air through molten pig iron to burn away impurities. His goal was to reduce the cost of steelmaking for military ordnance, and he succeeded his method made steel easier, quicker, and cheaper to manufacture.

The Bessemer process completely revolutionized structural engineering; however, Bessemer didn't stop believing in a better method. In 1865 he filed a patent for casting strips of steel directly, rather than casting the steel into ingots (bricks) first, which then had to be reheated and shaped by rolling machines. His idea was to pour the steel between two contrarotating, water-cooled rollers. The rollers would then squeeze the metal into sheets. However, despite the potential savings for both time and money, it was a difficult thing to make happen, so efforts to commercialize his patent were given up.

But this ain't your 19th-century steel manufacturing, anymore.

Since the 1850s, the only real change to undergo the steel industry in such a way was about a century later with the introduction of continuous casting. Continuous casting, which came about in the 1950s, is the process where molten steel is poured through a mold and cooled by water. It's then partially solidified into a semifinished " billet, bloom, or slab, to then be subsequently rolled in the finishing mills. Continuous casting improved the yield, quality, and cost efficiency of casting steel.

But continuous casting still requires a lot of rolling to get the steel thin enough as required by many producers; while a slab might be 80-120mm thick, producers such as car makers might require the steel to be 1-2mm thick. That's a big difference and a lot of energy consumption. But casting the steel thinner isn't really possible this way due to quality problems and microstructural flaws.

This is where Bessemer's decade-and-a-half-old idea comes into play.

Advances in steel production technology have made Bessemer's 1865 patent idea possible.

Castrip

The Castrip process produces flat-rolled steel sheets at thin gauges without the need for rolling partially-solidified slabs of metal.

Much like Bessemer's original patent, liquid metal goes through two copper water-cooled, counter-rotating rolls. A refractory core nozzle distributes molten steel into the melt pool while side dams contain the melt pool. The dual rollers move as the steel cools and solidifies. At the end of the process, the steel is only a few millimeters thick and requires minimal (if any) additional rolling.

Nucor, an American steelmaker, is utilizing the Castrip process in two of its plants (Nucor Steel Indiana and Nucor Castrip Arkansas). According to the company, the benefits of Castrip include a 70% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, faster production times, and cheaper operational and production costs.

The potential applications for this type of manufactured steel include furniture, non-exposed automotive products, fencing, roofing, appliances, and packaging (such as oil drums).

Shagang, a Chinese steelmaker, is looking to replace less energy-efficient plants with new technology, and a startup company called Albion Steel is also looking to build a Castrip plant in Britain.

Single Belt Casting

Besides the Castrip process, another method being tried involves casting liquid steel directly onto a single horizontal belt. Single-belt casting, like twin-roll, involves moving molds the belt moves with the steel as it cools and solidifies.

A German steelmaker, Salzgitter, opened the very first commercial single belt-caster in 2012. Initially, they made construction steel, but have begun working with more specialized steel.

SMS group, a construction engineering company, produces Belt Casting Technology for the metallurgical industry.

The Future of U.S. Steel?

Naturally, some of the issues regarding steel production in-country involve cost, efficiency, and even space. Fortunately, these cast-as technologies offer pros for all of those categories. If a car manufacturer, for example, could efficiently make their own steel components that are both of higher quality and cheaper there's much more incentive to integrate these types of mills within the factory, especially when space and energy consumption are not massive chunks of the equation.

To revamp the American Steel industry, a facelift might be in order just like with the Automotive Industry.

Sources:

http://www.economist.com/news/business/21718545-150-year-old-idea-finally-looks-working-new-technologies-could-slash-cost-steel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Bessemer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continuous_casting

http://www.cnn.com/2016/03/23/opinions/american-steel-industry-gibson-schmitt/

http://money.cnn.com/2017/03/01/news/china-trump-coal-steel-jobs/

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-03-08/steel-delivers-big-pay-off-long-before-trump-spends-1-trillion

http://www.steeltimesint.com/news/view/us-steel-to-shut-down-lorain-ohio-tubular-steel-production

http://www.castrip.com/Advantage/advantage.html

http://ietd.iipnetwork.org/content/casting

https://www.sms-group.com/plants/all-plants/belt-casting-technology/