Dive into the Internet's Undersea Cables

By on Jan 29 2018

Today's internet connection is essentially wireless and can be used in almost any location through wi-fi hotspots. Phones, tablets, and laptop companies often advertise on platforms relating to instant access to social media, faster internet connection, and even devices with their own wi-fi network installed into cars.

While our daily interaction with the internet is wireless, an intricate system of cables still makes connecting to the internet possible we just don't see them because they're underwater.

The Underwater Cloud

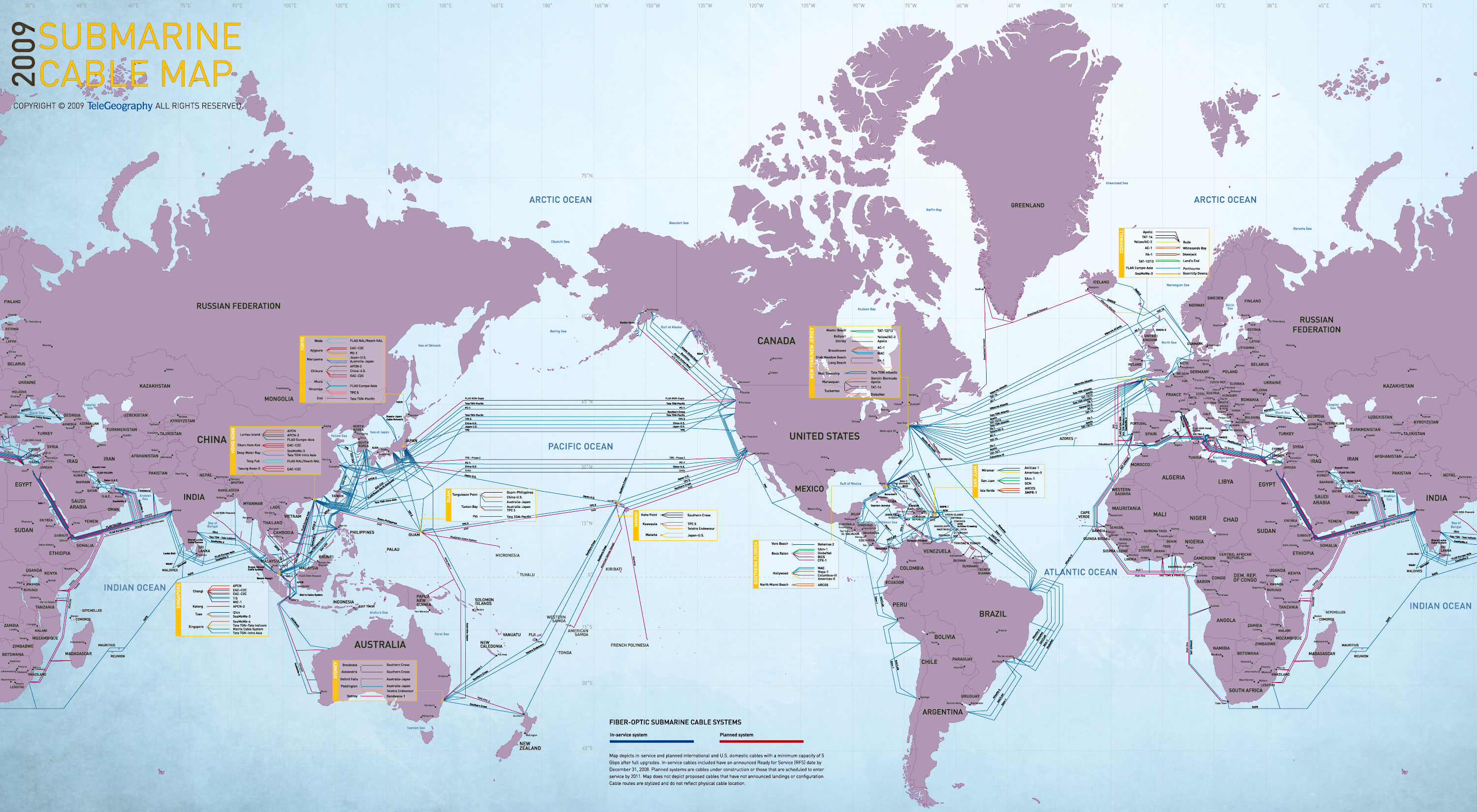

Cables laid on the ocean floor between continents are known as undersea or submarine communication cables. They transmit a bulk of information and provide users with instant internet access, phone calls, and television transmissions. While the idea of storing information and data on the cloud " has integrated with nearly every major information storage interface, "the cloud" actually exists underwater.

It all started when William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone introduced the telegraph in 1839. The invention was revolutionary, but the thought of having cables lie on ocean floors to connect different nations seemed like a futuristic idea that just wasn't possible yet.

However, in the early 1840s, Samuel Morse set up a telegraph wire underwater in the New York Harbor. The Morse code inventor insulated wire with hemp fibers and Indian rubber. Wheatstone set up a similar experiment in a Swansea bay off the coast of Wales with the same protective material and proved to be successful.

With many more instances of trial and error, commercial cables were eventually set up successfully and connected the whole world. The 1980s brought along fiber optic cables that rely on a solid state optical amplifier to comprise a signal. The only continent not to be reached by submarine communication cables is Antarctica because there is not yet a cable that can withstand -112 F and sweeping ice.

Installing Submarine Communication Cables

Laying the state-of-the-art fiber optic cables is both fascinating and tedious.

Cable-laying ships can carry cables up to 1,242 feet and follow plans made by the cable operator. The ships slowly place the cables on the seabed and can lay from 62-93 miles of cable per day depending on underwater environmental factors.

It begins at the landing station where cables are attached to a landing point before extending a few miles into the sea. Cables are fed into a plow that lays it into a trench as the ship moves across the ocean.

Each project costs between $100M and $500M, which is the most affordable method to transport terabytes--satellite installation cost exceeds 1 billion dollars.

If a cable needs to be repaired, divers or small, remote-controlled submarines go to the site and investigate the damage. Divers or robotic arms connected to the small submarine will bring damaged parts to the surface so they can be fixed.

SEA-ME-WE 3 and More

The longest optical submarine telecommunication cable connects Southeast Asia (SEA), the Middle East (ME), and Western Europe (WE) together. It extends from north Germany to Australia to Japan. French and Chinese companies promote the cable connection, and it is administered by the Singapore government. The countries completed the project in 2000.

It is 24,000 miles long, has 39 landing points, and relies on specific transmissions designed to produce a high-quality signal.

As of late 2017, the cable provided one of Australia's main connections to Asia. However, a cable of that length has brought along some issues. A repair ship was assigned to the detected damage location and repaired in early January 2018.

Tech and non-telecom companies are also getting involved in the sea cable business. Microsoft and Facebook installed a 17,000-foot cable beneath the surface. They completed the project in September 2017 and the cables transport 160 terabits of data per second. Google also recently announced plans to add three new undersea cables next year to expand its power in cloud computing.

View the world map of undersea cables here!

Sources:

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/how-are...